“When one tugs at a single thing in nature, he finds it attached to the rest of the world.”

--John Muir

So, too, with bees.

The rules for the organic certification of honey point to the dilemma of trying to live a healthy life in the 21st century. For starters, an organic bee hive must be no less than 2 miles distant from any recognized source of any kind of substance on a lengthy list of inputs which would contaminate the honey supply – this includes things like any agricultural facilities where chemical fertilizers, pesticides or herbicides are employed, and also includes things like plastics processing facilities, plants producing fire-retardant chemical foams, petrochemical facilities, even something as seemingly innocuous as a maraschino cherry packing plant. And organic honey from an urban bee hive? Forget it. Not going to happen – not unless you convince your city to give up automobiles, air conditioning, lawn fertilizers, hairspray, and probably electricity.

There has been a considerable increase in interest in backyard beekeeping since the introduction to popular consciousness of terms like “colony collapse disorder” and “Varroa mites”; paralleled with an increased interest in local foods and sustainable agriculture, one would think sustainable beekeeping would be on everyone’s lips.

One would be wrong.

Not only are beekeepers faced with the aforementioned organic obstacles, but “natural beekeeping” is not really all that popular an approach, either. At least, it hasn’t been historically. Myrtle is jumping on a bandwagon which has just left the station, however, in the form of an ancient method which is making a comeback. It goes by the nifty handle Top Bar Beekeeping.

Basically, the default setting for any information search on how to start keeping bees will reference a type of hive which has had almost unanimous market share ever since it was invented – the Langstroth hive. This is the contraption most people immediately envision when thinking of beehives, complete with the keeper in his hazardous materials suit and thick mesh veil. But bees have been “kept” for thousands of years, and the boxes of hives (built for suitability to human purposes, not the health and happiness of the bees themselves) have only been around for less than two centuries.

What did people do in order to harvest honey prior to the invention of the Langstroth boxes?

The earliest honey harvesters, of course, simply raided natural hives in trees. And if you want to be a “natural” beekeeper, this would seem to be the most natural method. A little compromise seems in order, though, given that there is no way to harvest the “natural” hive without destroying it.

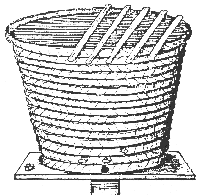

The next step up was a type of hive called a “skep” and this is the type you’ll find in much of Eurasia to this day – it is basically a “wild” hive in form, like an upright log or a clay pot or some such, covered with a straw “hat”. Much like wild honey, however, honey in a skep can only be harvested by destroying the hive.

The final step on beehive evolution before we get to the “modern” hive is the top bar hive – literally just a box (sizes and dimensions varying from place to place and culture to culture) with bars across the top, along the bottom of which the bees build their honeycomb just as they would in a tree.

The chief advantages to the top-bar method (as compared to wild honey harvesting) involve the ability manipulate the bars – that is, you can take out one bar at a time and (after gently brushing off the bees) cut off the comb and harvest the honey and wax.

Langstroth hives are the technological “advance” from this concept, wherein bees are forced to build their comb on a frame, going up rather than down and in a square rather than in a naturally drooped comb. In addition, numerous “improvements” on bee culture have been made in Langstroth hives, including the ability to sequester the queen in one section of the hive so that brood only inhabits certain parts of the comb, leaving other parts to be entirely comprised of honey.

Langstroth hives, in short, are built for maximum production for humans. Top bar hives are built as a compromise position, allowing the bees to behave as naturally as possible while still allowing for human consumption.

Which approach is more likely to be healthy for the bees, and as a consequence, for the surrounding environment?

If you have to ask which we would prefer at Myrtle’s place, you haven’t been paying attention. Langstroth hives are symbols to us of all that is wrong with the human relationship to our food sources. It is little wonder to us that in an era when billions of dollars are spent on apiculture, Varroa mites and various bacteria, parasites, and viruses contrive such a thing as colony collapses.

Bees, in short, are smarter about apiculture than people could ever hope to be.

Case in point – next time you venture near an herb garden, pay especial attention to which flowering herbs attract the most bees. Some are obvious – basil (particularly the pungent anise-flavored basils such as African Blue) will literally buzz because the bees love them so much. They are rich sources of pollen, and it is only natural that the bees should love them.

Other plants, though, like lavender, are also buzzing, in spite of not being a tremendous food source for bees (or any other insect, for that matter). Lavender has a great deal of nectar proportionally to the size of its blooms, but those blooms are rather small, and they are chock full of irritating oils to boot; and while it smells lovely to humans, lavender is not particularly appealing to bees, who only make lavendar honey when (such as is the case in much of France) humans force them to by monocropping the plant for miles and miles. Why would bees flock – in rather impressive numbers – to a plant that does not provide them with the nutrients they need?

The reason bees flock to lavender, it turns out, is that lavender is noxious to mites. Commercial beekeepers use many tons of chemicals every year to combat Varroa mites, with the result that they are genetically selecting stronger and stronger mites, and putting poisonous chemicals in their honey. They ought to instead be spending much less money to plant natural remedies around their bee fields – lavender, juniper, cedar, creosote, and a host of other plants which in addition to making the bees healthier, make their honey tastier.

Unsustainable practices such as chemical treatment for mites are a natural consequence, though, of the shape of agriculture generally, not just of apiculture. The vast majority of bees in this country are kept not for honey production, but for pollination. Huge flatbed truckloads of Langstroth boxes go flying down our highways and byways each season chasing after the next crop needing fertilization.

Doesn’t this strike anyone else as just plain odd? Why do we have to truck in bees to pollinate our almonds and apples and peaches? Don’t answer, it was rhetorical. We know what the industry says – it is “more efficient” to mass produce monocrops using trucked-in bees.

But the fruit doesn’t taste any better. It isn’t as nutritious. And the honey, frankly, sucks.

Wouldn’t it be better to have smaller hives in smaller orchards, producing better food?

We certainly think so. We have been privileged to live on the same half-acre as a wild hive for the last five years, and have only a couple of stings to show for our nosiness. We plan on offering our bees a new home this Spring, a 30” top-bar hive of our own construction, with a viewing window on the side. In exchange for letting us have some of their honey and beeswax, we hope to make our bees as safe and snug as we possibly can. Maybe not organic, maybe not even entirely natural, but a fair sight better than what we see going on in American agriculture generally. We’ll keep you updated.

Happy farming!

No comments:

Post a Comment