“We scientists are clever – too clever – are you not satisfied? Is four square miles in one bomb not enough? Men are still thinking, ‘Just tell us how big you want it.’”

– Richard Feynman

– Richard Feynman

“As a guide to engineering ethics, I should like to commend to you a liberal adaptation of the injunction contained in the oath of Hippocrates that the professional man do nothing that will harm his client. Since engineering is a profession which affects the material basis of everyone’s life, there is almost always an unconsulted third party involved in any contact between the engineer and those who employ him – and that is the country, the people as a whole. These, too, are the engineer’s clients, albeit involuntarily. Engineering ethics ought therefore to safeguard their interests most carefully. Knowing more about the public effects his work will have, the engineer ought to consider himself an ‘officer of the court’ and keep the general interest in mind.”

– U.S. Navy Admiral Hyman G. Rickover

The line between science and engineering has been blurred for a long time now, probably irrevocably. What passes for “science” in many university laboratories these days is little more than one form or another of engineering – how to create vaccines that fight particular viruses, what materials make the best semiconductors, or the best solar panels, or the lightest plastics, or the strongest panes of glass. These are manufacturing studies, not science studies.

The worst offender for this abandonment of the respective responsibilities of the scientist (who ought be concerned with little more than the secrets of the universe) and the engineer (who takes the knowledge scientists offer and turns it into useful products) is the realm of what often gets called “agricultural science” – an offensive term if ever there were one.

– U.S. Navy Admiral Hyman G. Rickover

The line between science and engineering has been blurred for a long time now, probably irrevocably. What passes for “science” in many university laboratories these days is little more than one form or another of engineering – how to create vaccines that fight particular viruses, what materials make the best semiconductors, or the best solar panels, or the lightest plastics, or the strongest panes of glass. These are manufacturing studies, not science studies.

The worst offender for this abandonment of the respective responsibilities of the scientist (who ought be concerned with little more than the secrets of the universe) and the engineer (who takes the knowledge scientists offer and turns it into useful products) is the realm of what often gets called “agricultural science” – an offensive term if ever there were one.

|

| Too clever by half... |

The study of plants is called “botany”. The study of animals is “zoology”. If you want to be a generalist who studies both, you are a “biologist”.

The study of how to create drought resistant crops through genetically altering existing plants, or new chemical combinations that more effectively deter pests or weeds… that should more properly be called “agricultural engineering” and it has a whole different set of ethical considerations from science, as Admiral Rickover so ably pointed out. He was only wrong in one respect in his evaluation – the “3rd party” he describes is not merely the entirety of the human population, it is the sum total of all life on Earth.

Farming is a roughly 10,000 year old invention. It has altered the planet more radically than any previous human invention, and arguably any field of endeavor since. Being responsible for the consolidation of human beings into larger and larger communities, one could easily make the argument of causality between early man defending stands of einkorn grain in prehistoric times, thereby ending their days as hunter-gatherers, to the fouling of our land, air and water caused by all of the pollution attendant upon the Industrial Revolution, not to mention truly horrifying things like war, crime, and reality television.

We did not stop at merely establishing local borders around our favorite wildly available crops, of course. We began cultivating them, and even if some contemporary religious fanatics have a hard time accepting the reality of the Theory of Evolution… early man knew full well how natural selection works – and took full advantage, teasing crops along through selective breeding generation after generation.

Numerous plants we take for granted in our gardens only exist because of anthropogenic botanical evolution, in fact. One of the most common crops in American culture – both for large-scale monoculture industrial farming, and for home gardens – is corn (maize, to most of the world). 10,000 years ago, it did not exist. But numerous farmers in Central America and Southern Mexico noticed that certain tall grasses had useful succulent seed-kernels, and after selecting those with the most numerous and tightly bunched, generation after generation, came up with grasses that featured “cobs” (stumpy at first, but once they’d gotten to this point, the next phase of their agricultural engineering was obvious – bigger cobs, with sweeter kernels).

Early agricultural engineering has itself evolved, to the point where we are no longer satisfied with selectively breeding plants with desirable genetic traits – no, we are going straight to the source, and altering the DNA directly. In addition, we are refining our treatment of not just the plants, but the soil, water and air surrounding our crops, in attempts to limit the natural effects of nutrient depletion, drought (or flood), competing plant-life, and herbivorous animals (both vertebrate and invertebrate).

Michael Crighton’s best-selling “Jurassic Park” featured an experiment in genetic engineering which lay towards the ridiculous end of the “suspension of disbelief” continuum, and yet… there are lessons in his fictionalized account of biological engineering run amok. Ian Malcom, Crighton’s cantankerous fictional skeptic, coins a term for genetic engineers (and others who share their optimistic outlook for their form of technology): “Thintelligence” – loosely defined, it is the ability to figure out how to do something, especially something very clever while lacking the ability toknow whether or not it ought to be done.

For the time being, we will ignore the question of genetically modified crops – there is certainly plenty of material for discussion there, including but not limited to potential health hazards, declining nutritional value of the food items in question, and the ridiculous notion of patented DNA sequences carried over into patent violations caused by fertilization of other people’s crops (basically, neighboring farmers can be sued because pollen from a field with GMO crops blew in, without the 2nd farmer’s approval… causing his crops to have “unauthorized” DNA sequences).

Instead, we wish to highlight the folly – and, in fact, the lack of engineering ethics – in the objectives of the vast majority of forms of engineered agricultural solutions.

The most thoroughly documented (because it was the first to come to the attention of environmental scientists, who were much more interested in studying the effects of these inventions than were the engineers who made them) are the chemical herbicides and pesticides which have been de rigueur in the agricultural industry (and all too often in home gardens) for over a century now.

Some, of course, have long been illegal – the herbicide known as Agent Orange was manufactured by Monsanto and Dow Chemical for the express purpose of being used as an herbicidal defoliant with military applications, and its widespread use in the Vietnam War led directly to numerous chemical burns and long-term health problems including almost epidemic cases of cancer among veterans of that war. Additionally, of course, it proved ineffectual both as a tactic (Viet Cong food supplies were only slightly diminished, owing to the dispersant character of rice farming, where affected waters were simply replaced with newly irrigated fields) and also as a practical engineering solution – the concept of clearing away massive swaths of jungle to make guerilla warfare difficult ignored the reality that not every plant defoliates precisely the same way – they managed to change the level of biodiversity in the jungle, but they did not kill it.

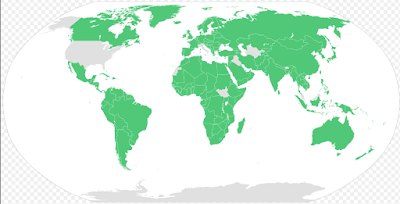

Likewise, the use of DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), a 19th century chemical invention the use of which as an anti-mosquito pesticide was developed by Swiss chemist Paul Hermann Müller in 1939, had numerous unhealthful side-effects; it was largely responsible for the near extinction in the 20th century of the bald eagle and the peregrine falcon, in addition to causing numerous health complaints in humans. In 1962, Rachel Carson penned Silent Spring, the seminal environmental work which eventually lead to a ban on DDT in the United States, and was the forerunner to the eventual 2004 Stockholm Convention, which outlawed several persistent organic pollutants. The Convention has been ratified by more than 170 countries and is endorsed by most environmental groups.

Some, of course, have long been illegal – the herbicide known as Agent Orange was manufactured by Monsanto and Dow Chemical for the express purpose of being used as an herbicidal defoliant with military applications, and its widespread use in the Vietnam War led directly to numerous chemical burns and long-term health problems including almost epidemic cases of cancer among veterans of that war. Additionally, of course, it proved ineffectual both as a tactic (Viet Cong food supplies were only slightly diminished, owing to the dispersant character of rice farming, where affected waters were simply replaced with newly irrigated fields) and also as a practical engineering solution – the concept of clearing away massive swaths of jungle to make guerilla warfare difficult ignored the reality that not every plant defoliates precisely the same way – they managed to change the level of biodiversity in the jungle, but they did not kill it.

Likewise, the use of DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), a 19th century chemical invention the use of which as an anti-mosquito pesticide was developed by Swiss chemist Paul Hermann Müller in 1939, had numerous unhealthful side-effects; it was largely responsible for the near extinction in the 20th century of the bald eagle and the peregrine falcon, in addition to causing numerous health complaints in humans. In 1962, Rachel Carson penned Silent Spring, the seminal environmental work which eventually lead to a ban on DDT in the United States, and was the forerunner to the eventual 2004 Stockholm Convention, which outlawed several persistent organic pollutants. The Convention has been ratified by more than 170 countries and is endorsed by most environmental groups.

|

| The countries in green have agreed to ban persistent poisons in farming; the ones not in green have not. Notice the biggest one? |

Sadly, the United States, Israel, Malaysia, Italy and Iraq (all significant agricultural producers) are not signatories – while DDT is banned in the United States, and our overall use of agricultural pesticides has dropped slightly in the last decade, the U.S. still used (as of 2007, the latest figures we could find) 1.1 billion pounds of pesticides, comprising 22% of the world’s total. There are over 20,000 pesticide products marketed in the United States.

And yet… the health effects of a disturbingly large percentage of these products are largely unstudied, especially in longitudinal studies which are, after all, the only way to gather data about the accumulation of these chemicals in our bodies, and the possible long-term conditions caused thereby. Engineering methods (designed to get “useful” products to market as quickly as possible) disguise themselves as scientific investigations, where a short-term study finds no problems, and Monsanto and Dow get to fire up the production lines. Engineering ethics, as described by Admiral Rickover, are not a concern – after all, it’s science, right?

And yet… the health effects of a disturbingly large percentage of these products are largely unstudied, especially in longitudinal studies which are, after all, the only way to gather data about the accumulation of these chemicals in our bodies, and the possible long-term conditions caused thereby. Engineering methods (designed to get “useful” products to market as quickly as possible) disguise themselves as scientific investigations, where a short-term study finds no problems, and Monsanto and Dow get to fire up the production lines. Engineering ethics, as described by Admiral Rickover, are not a concern – after all, it’s science, right?

Additionally, the effectiveness of these products is debatable. Both healthfulness and effectiveness are serious questions – most users of pesticides lightly brush aside questions of runoff, yet it is not only inevitable, it is as obvious as the idea that the sun is more visible on a clear day than a cloudy one. Chemicals on a plant wash off in the rain, or via most forms of irrigation. They go either into the soil, and then seep into our groundwater, or they drain into creeks and rivers, lakes and oceans. There is no “away” to which these substances can go – and the fact that those who apply them have to wear protective masks should be our first clue that maybe we should not want them to be used at all.

The World Health Organization and the UN Environment Programme estimate the number of agricultural workers who suffer health effects from pesticide poisoning each year at 3 million. 18,000 agricultural workers die each year from the “marvel” of agriculturally engineered pesticides.

The worst part? In the long term, these chemical concoctions do not work as well as approaches designed to work withnatural forces instead of against them. The use of organic pest control solutions is a wide-ranging field, including application of capsaicin-laced concoctions designed to deter rodents and other mammalian foragers, application of symbiotic nematodes and bacteria which work with the plants to deter insects and diseases, companion planting to deter both competing plants (usually erroneously described as “weeds”) and foraging insects, the use of beneficial insects such as ladybugs, the inclusion of bat-houses in agricultural architecture… the list of natural solutions is lengthy… and more importantly, is both healthy and effective.

One of the chief aims of biological pest control, in fact, is the maintenance – and active encouragement – of biodiversity. Obviously, this approach will not work for large-scale monocropping, which is one of the most important reasons for large-scale monocropping to disappear from the planet.

Biodiversity is important because it drastically reduces predation without opening new ecological niches for either resistant varieties of the existing pest (that is, natural selection causing only those varmints, bugs, pests, etc. who are immune or less-affected by the poison to be the only ones capable of breeding the next generation, who will then be even less likely to be affected, eventually rendering the poison ineffective), or opening up the opportunity for invasive species who more than likely are not targeted by nor affected by the existing poison treatment.

Basically, life finds a way – if your plan is to keep anything from eating your crops at all, well, newsflash, you keep one thing from eating them, something else will take its place.

In a biodiverse agricultural system, however, the goal is not elimination of predation, the goal is to place predation in a more natural, and therefore tolerable, context. Sure, it requires more work (planting trap crops, for example, like rows of sunflowers or amaranth around your rows of corn, and planting fields of clover between your melons and cucumbers), and harvesting is done more by hand than by machine, but the yields per acre over the long term are much higher. Why? Because specific acreage is orders of magnitude less likely to “play out”.

Monocropping systems have certainly increased yield per acre for a specific growing season or year, but over the course of five, ten, twenty, or fifty years, the acres in question become wastelands of infertile ground. An organic permaculture farm where crop plants are treated with respect as a significant part of a wider ecosystem will continue producing indefinitely.

Which is the difference between intelligence and thintelligence. The end game is what matters, and if we ever want to get there, we need to stop pretending that new inventions are “discoveries” – they aren’t science, they are engineering. Impressive, maybe, but only useful if they first do no harm.

Here’s hoping more agriculturalists hop on board the biodiversity train and abandon the chemical-engineering road to perdition.

Happy farming!

Biodiversity is important because it drastically reduces predation without opening new ecological niches for either resistant varieties of the existing pest (that is, natural selection causing only those varmints, bugs, pests, etc. who are immune or less-affected by the poison to be the only ones capable of breeding the next generation, who will then be even less likely to be affected, eventually rendering the poison ineffective), or opening up the opportunity for invasive species who more than likely are not targeted by nor affected by the existing poison treatment.

Basically, life finds a way – if your plan is to keep anything from eating your crops at all, well, newsflash, you keep one thing from eating them, something else will take its place.

In a biodiverse agricultural system, however, the goal is not elimination of predation, the goal is to place predation in a more natural, and therefore tolerable, context. Sure, it requires more work (planting trap crops, for example, like rows of sunflowers or amaranth around your rows of corn, and planting fields of clover between your melons and cucumbers), and harvesting is done more by hand than by machine, but the yields per acre over the long term are much higher. Why? Because specific acreage is orders of magnitude less likely to “play out”.

Monocropping systems have certainly increased yield per acre for a specific growing season or year, but over the course of five, ten, twenty, or fifty years, the acres in question become wastelands of infertile ground. An organic permaculture farm where crop plants are treated with respect as a significant part of a wider ecosystem will continue producing indefinitely.

Which is the difference between intelligence and thintelligence. The end game is what matters, and if we ever want to get there, we need to stop pretending that new inventions are “discoveries” – they aren’t science, they are engineering. Impressive, maybe, but only useful if they first do no harm.

Here’s hoping more agriculturalists hop on board the biodiversity train and abandon the chemical-engineering road to perdition.

Happy farming!